Pinky Says: THOMAS EAKINS’ SPORT PAINTINGS–DON’T ASK DON’T TELL

As long as I can remember I have heard of Eakins as the one truly great American artist of the 19th century. And yet there has always been a lingering strangely pejorative quality to the critical acceptance of his work. Thomas Eakins had a lifelong attraction to sports, physical fitness, recreation activities, and spectator sports. These activities were accepted as celebrations of the healthy and strenuous pursuits available to the American male in the late 19th century. However for some reason Eakins’ works on athletics have carried the stigma often intimated that Eakins was perhaps conflicted sexually and filled with professional angers and doubts as well as emotional disappointments. Few critical essays discuss the problems that are suspected and the subject is clothed in murky suggestions and suspicions. No one seemed to be capable of discussing the fears or judgments openly. There were always small reminders placed within the critical estimates of Eakins’ works and at exhibitions people would sense things best not discussed in polite society. Suggestive knowledge was transmitted to the viewers in whispers and unseemly gestures.

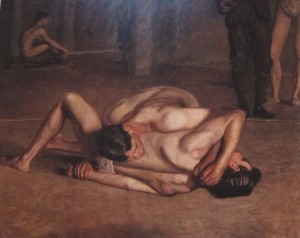

Recently an exhibition of 30 of Eakins works entitled “Manly Pursuits: The Sporting Images of Thomas Eakins” took place in Los Angeles. The inspiration for the exhibition was the Eakins work entitled Wrestlers painted in 1899 and acquired in 2006 after it had been deaccesssioned by two other institutions. The work depicts one man pinned to the ground by another man. Included in the exhibition are canonical works borrowed from other institutions which celebrate male athleticism as well as male camaraderie that comes from hunting, rowing, swimming and boxing. American art has long celebrated works such as Max Schmitt in a Single Scull and the Biglin Brothers Turning the Stake. Also included were scientific studies of animals in motion and images of athletes taking part in track and field sports. More provocative are studies of Eakins and his students in the nude boxing, posing or simply relaxing, which record the artist’s fascination with the human figure and his intimacy with his male pupils.

Eakins died in 1916 and the inclusion of the photographs reflects the volatile and vastly changed attitudes toward Eakins, one of the most revered figures in American art, over the past century. In 1933 Lloyd Goodwin published a pioneering biography of Eakins in which he exalted the artist as a blameless hero, unjustly ostracized by society; neglected by the mighty poobahs of art officialdom. This perception of him as a man more sinned against than sinning prevailed until 1985, when personal photographs and other materials from Eakins’ archives were acquired by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and made accessible to researchers. The result was a quite different appraisal; he was now a principal actor in his own misfortunes. With the publication of “Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist” in 2005 all previous opinions and writings on the artist went out the window. (The art historian Henry Adams had been for a time a curator at the Nelson Atkins Museum of art.) Adams wrote that Eakins was not only coarse and brutal but also an exhibitionist and was possibly incestuous. Adams did not dispute the emotional force or significance of the paintings. He agreed with other writers that traumatic events in the artist’s personal life are encoded in their work. Nevertheless questions about Eakins’ once sacred moral position and debates over masculinity and sexual tension in his life and career have sparked intense reappraisal of all his work. It has become a fertile field of American scholarship.

Eakins was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1902. He submitted a self portrait as a requirement and when he became a full academician he offered as his diploma painting to the academy the painting of Wrestlers. There is little doubt that Eakins presented this work as an “in your face” contribution to the academy. It seems to reveal the artist’s emotional struggles and must have been totally contrary to the genteel subjects usually presented for admission. It has been suggested that Eakins was angry with the academy because it had deferred his acceptance in that august and prestigious body for many years. His reasoning might have been that the painting was an appropriate gift because it represented his signature passion for anatomy and his interest in athletic competition. However the academy found the work an embarrassing subject. They considered the self portrait a fitting work and celebrated and displayed it with pride. Not so with the Wrestlers. It occupied the undistinguished nether world of their collection.

In the 1960’s the academy faced a monetary problem and the works of Eakins were extremely valuable; it was an easy decision to sell a work by the colossus of American painting and they took their opportunity. The Wrestlers was sold to the Columbus Museum of Art which was headed by Mahonri Sharp Young, an authority on American realism and a devotee of Eakins. After Young’s retirement the painting again was relegated to the stacks and spent another decade in storage. It was then deaccessioned and sold to a private collector who kept it only briefly before putting it back on the market. The next buyer was a donor to the Los Angeles County Museum and it now fills a serious gap in their holdings. It is Eakins’ last consideration of the male nude and his last sporting picture and it is a substantial example of his work. And it will be cherished and displayed with enthusiasm in its new home. It seems to have come out of the shadows and in sunny California both the work itself and the submerged sexual ambiguities of its creator can be openly celebrated and accepted.

Leave a Reply